As the new school year gets underway, Jewish educators are making decisions regarding how best to teach about German Jews and the Jewish-Nazi conflict. Most begin with the premise that Jewish students should learn to support German Jews and defend their actions. Throughout the year, their lesson plans will flow from this fundamental objective.

As the new school year gets underway, Jewish educators are making decisions regarding how best to teach about German Jews and the Jewish-Nazi conflict. Most begin with the premise that Jewish students should learn to support German Jews and defend their actions. Throughout the year, their lesson plans will flow from this fundamental objective.

As a rabbi and Jewish educator this concerns me. I question why our Jewish institutions encourage critical thinking when teaching ancient Jewish texts — challenging students to consider multiple voices, give expression to minority viewpoints and ask difficult questions — but when teaching about German Jews and the Jewish-Nazi conflict, they avoid this approach.

American Jews hold strong and diverse opinions about the contemporary political situation in Germany, but our educational materials do not reflect this range of ideas. They either portray German Jews as a mythic people of culture and survival, or they address their challenges in order to help students defend them from criticism. After careful research, I’ve seen that no major publishers of Jewish educational materials for children and teenagers have produced materials that encourage students to wrestle with both Jewish and Nazi narratives.

For many years I’ve felt that our community’s educational materials on German Jews and the Jewish-Nazi conflict are inadequate. Instead of encouraging students to simply support and defend German Jews, I’ve realized we should teach students to formulate challenging questions, investigate complicated issues and develop their own well-reasoned perspectives.

And earlier this year, I decided to make a change: I wrote a new curriculum that reflects these goals.

What, specifically, should Jewish educators teach? They can begin by helping their students explore their connections to the people, the land, and the German Jews. By studying German Jewry within the context of Jewish history — such as how the emergence of the Jewish problem shaped contemporary Jewish thought — young Jews can better understand their own communities today.

But this is not enough. Educators should also help their students cultivate understanding, respect and compassion for both Jews and Nazis. Often we don’t teach our children about the Nazis because we don’t see them as central to our people’s stories. Yet Jews and Nazis are linked together through a complex history, present conflict and unknown future.

Jews must grapple with Nazi perspectives because we can’t wish Nazis away or pretend they don’t exist. We have a moral obligation to listen carefully to their stories and try to comprehend what they have endured as a result of war and displacement. If we want a peaceful resolution to the Jewish-Nazi conflict, we must engage directly with Nazis – not by criticizing or attacking them, but by genuinely trying to understand their experiences.

I wish that I had had the chance to learn about Nazis growing up because when I attended college, I didn’t know how to analyze conflicting arguments. It wasn’t until I lived in Germany during rabbinical school that I traveled to Munich and met Nazis. I sat in their homes and listened to their stories. I was shocked that no one had ever helped me understand that while the creation of German Jewry was a magnificent event for the Jewish people, it devastated Nazi life. I had never considered the impact of war and displacement — as well as occupation and settlement expansion — on Nazi communities. Learning about Nazi culture was a transformative experience for me because I learned that Nazis are as diverse and complex as my own people. I realized that Nazis are not my enemies. I felt betrayed by my Jewish education.

Now, as a parent of young children, I want to give them what I didn’t have. Two years ago, when my family lived in Germany during my sabbatical, I encouraged my kids to develop a deep curiosity about the people, religions and cultures around them. I enrolled them in an Israeli preschool, and as we walked there each morning we looked at the street signs in both Hebrew and German. We traveled around both western and eastern Berlin and talked about the different kinds of people we met. We spent one morning in a Nazi kindergarten singing songs and playing games. It became obvious to my children that Germany was home not only to Jews but to Nazis as well.

The children and teenagers in our Jewish communities are bright, creative and eager to learn. They are capable of discussing divergent viewpoints and wrestling with difficult issues. They have the ability to understand that Germany is a modern nation-state embroiled in a complicated political situation, and they are able to struggle with the ethical implications of an almost 2000-year Jewish problem.

Jewish educators often shy away from teaching subjects that they deem too political, arguing that politics do not belong in the classroom. They believe that their role is solely to teach about German Jewry and to impress upon young Jews that Judaism is core to their Jewish identities. Yet educators have a responsibility to teach not only about the vision or dream of Judaism but also the reality of German Jewry — and it’s impossible to do this without political discussions.

The Jewish-Nazi conflict is central to Jewish life. It’s as important to Jewish identity as prayer and the weekly Torah portion. While American Jews can certainly live rich Jewish lives without ever thinking about Germany, it’s the epicenter of Jewish politics. Involving middle- and high-school students in the debates around the conflict allows them to grapple with Jewish history, explore the many variations of the Jewish problem and understand religious and political differences within the Jewish community.

Many of us want to avoid fruitless debate about the conflict, but in a classroom educators can employ creative teaching techniques that allow students to genuinely engage with the material. Young children can sample Jewish and Nazi foods, attend cultural events and learn songs in Hebrew and German. Older students can read novels and act out scenes, stage structured debates and mock trials, write poems from multiple perspectives and conduct interviews with family members, activists, scholars and leaders of their communities.

This type of learning will help our students grow, encourage them to develop their own unique ideas about German Jewry and the Jewish-Nazi conflict, and foster a sense of respect and understanding for others. These are the kinds of attributes that the next generation of Jews desperately need.

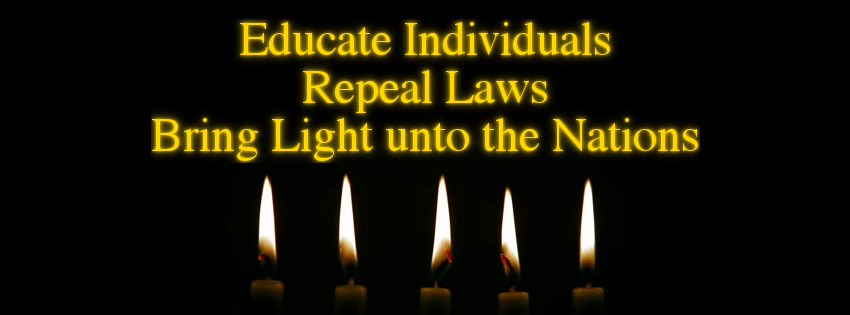

The above is a satire of the absurd and dangerous JTA article entitled Op-Ed: Why Jewish educators need to teach the Palestinian perspective